“Nationalism and environmentalism go hand in hand,” say the Homeland Party, one of the far-right groups who have gained recent prominence in recent months owing to their role in organising the often-violent protests against asylum seekers in Epping and elsewhere, “because we love our people and our land more than money or power.” Although I suppose it depends on what you mean by “our” people, and what you mean by “love” and “power.”

Homeland are a far-right splinter from a far-right splinter: of the BNP via Patriotic Alternative. While their parent organisation, PA, give off only a moderate whiff of blut und boden—“The UK”s beautiful and rich natural environment is part of our ancestral inheritance,” is the sum total of their environmental policy—Homeland go all in: greenbelt preservation, biodiversity, measures to curb pollution. They don’t approve of what they call “greenwashing” projects, like solar power, net zero, vehicle taxes, ULEZ or HS2. In fact, if you read on, it becomes apparent that Homeland’s environmental policies all circle one particular policy point: The greenbelt is being destroyed by population growth, which is driven by mass immigration. Biodiversity measures seem solely aimed at saving “the indigenous species of our homeland” (a comical comparison is made with New Zealand, which has about 96 endemic birds and mammals; England has none). And while it’s hard to argue against anti-pollution measures, in right-wing framings, as the Indian writer Mukul Sharma points out, “pollution dilutes and vitiates a hypothetically pristine socio-cultural fabric.” It’s always about purity.Subscribe

On these issues Homeland, for all that they are electorally negligible even with their increased publicity, may be tapping into a non-negligible current in right-wing thought. That same current informs the thinking of the Irish ethnonationalist influencer Keith Woods, who has come out in favour of “rewilding”. “To be an ethnonationalist,” Woods writes in his book Nationalism, “is to see some irreducible value in the unique forms of the natural world, and this extends from the natural world to the safeguarding of the unique world-sense of a people”—which, of course, requires a prompt end to mass immigration.

The right-wing mainstream has seemingly been outflanked here. Nigel Farage’s Reform UK (which could never with a straight face be said to care about anything more than money and power) has little to say about farming and the countryside. Farage himself will always show up at a farmers’ protest to stand next to a tractor in a wax jacket, but even the so-called “family farm tax”, which applied new thresholds to the taxation of inherited agricultural assets and is the only recent agricultural issue to have really cut through in Britain, was for Reform just a footnote to its longstanding policy on scrapping inheritance tax, to which Farage tacked on some blather about “ghastly” solar panels.

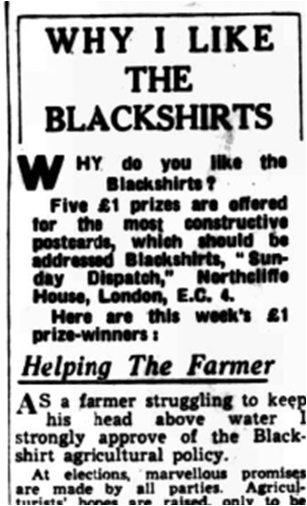

Farming has long played an important, if complicated, role in far-right conceptions of England. The English countryside is identified with the “traditional” values of social conservatism, racial purity and provincial self-sufficiency, values of which the farmer is the custodian and the soil, somehow the eternal repository. In the mid-1930s, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) embraced the potential of agriculture to serve their cause as both a flagship for their white-supremacist social policy and a likely market for their protectionist economics. Only a few years earlier, however, there had been a sense that old-fashioned farming was a poor fit for a dynamic, forward-looking movement like fascism (in his memoirs, Oswald Mosley reflected that “it appeared a mistake to maintain a way of life [farming] which seemed forever gone”); the historian John Brewer notes that “it was not until a year after its formation that the BUF showed any interest in agriculture”.

When it eventually did commit to the countryside, the trigger was predictably opportunistic. In February 1934, a contingent of Mosley’s Blackshirts descended on the village of Wortham in Suffolk to “protect” a local farmer, RH Rash, against “encroachment on his rights.” Rash was a holdout in the so-called East Anglian Tithe War, a co-ordinated programme of local resistance against land taxes. Rumours soon spread of a Fascist force of 500 men, giving rise to titters in the local press about “phantom Fascists”. In any case, it was a meaningful intervention; prominent local Nazi Ronald Creasy insisted that the BUF had been invited—on account of their experience in handling “Communist fuglemen”—but the Party was disavowed by the Suffolk Tithe Payers’ Association, and derided in court as a movement with “a foreign uniform, a foreign war cry and foreign methods of salute.”

Blackshirt mentality, now as then, always prioritised “action” over theory or democratic process. Even now, the far-right remains keen to hasten to the side of the downtrodden farmer when there’s a chance, however slim, that a fight might break out. Patriotic Alternative’s Joe Marsh could barely contain his excitement when in spring 2024 he warned of “big protests” by farmers across Europe. Orders had gone out from “the likes of the WEF, UN, WHO, and the EU”, according to Marsh, that the farmer must be destroyed (the global warming hoax and the bird flu hoax were all part of the plan). But farmers were fighting back. “Make sure you’ve got extra food supplies in,” Marsh warned.Subscribe

Marsh’s vision of an England “totally reliant on unelected billionaires for our most basic needs”, in which “we could be cut off, forced to ration and in the worst case face mass starvation at any time,” comes over like a mutant, conspiracist grandson of the claim that “we were destroyed by the system which crowds the people of Britain into offices and factories and leaves farming to the foreigner,” made in 1939 by the Fascist, Francis McEvoy. Marsh’s panicked prospect of mass starvation, meanwhile, recalls Viscount Lymington’s influential 1939 jeremiad Famine In England, in which the Fascist aristocrat and agriculturalist forecasts “panic, looting, revolution and wholesale bloodshed” should the country not look urgently to its food security (the looting and revolution would of course be caused largely by the subhuman “scum” of the cities, most of whom are “alien”, the “people of the ghetto and the bazaar”: Lymington was among the BUF”s fiercest racists, and remains something of a problem for those who would characterise the Blackshirts” green wing as hard-pressed yeomen with legitimate grievances).

***

Attempts throughout the 1930s to push Mosley as the farmers’ saviour are hard to read without thinking of Farage and his Barbour. But whatever progress the Blackshirts were able to make in farming communities tended to be undermined in tragi-comic fashion by the tin-eared monomania of the Fascist orator. When Mosley spoke at Worcester in 1934, Brewer reports, “farmers who came to hear their grievances aired were entertained to a tour through Fascism”; at Evesham, William Joyce (who became famous during the War as the Nazi propagandist “Lord Haw-haw”) spoke for four hours without once mentioning agriculture (and later led a procession of uniformed Blackshirts through the town singing the Italian Fascist anthem Giovinezza).

For Mosley, as for Farage, agriculture was subsidiary to a wider economic programme: farming could not be “saved” until “the whole national problem” was dealt with. BUF dogma—“this here Corporal State”, as a character puts it in Doreen Wallace’s Tithe War novel So Long To Learn—came first, and all else fell into line behind.

Besides, in many ways, decline, even to the brink of disappearance, was what farming was for. Fascism was in reality an urban movement. The BUF relied on London, Birmingham, the Black Country and industrial Yorkshire and Lancashire for the bulk of its support. East Anglia, whipped up by the Tithe War, was an outlier. The farmer was to the metropolitan fascist of the 1930s what the fisherman is to Farage today. He (and it was always a he) stands for what we have lost, or surrendered; he is both emblem and custodian of the traditions of the race, and of the values and virtues we have in our folly set aside.

There were Fascists, of course, who had genuine concern for agricultural matters, not least the prominent Blackshirts who were full-time farmers themselves: landowner Ronald Creasy in Suffolk; NUF stalwart Robert Saunders in Dorset; John Dowty in Worcestershire. Dowty maintained that “I had nothing to say on Jewish people; there was so much to say on the question of the land and farming.” Saunders was more of an ideologue—he was happy to supply an interested correspondent with an essay on the “New philosophy of Fascism” —but his diaries, BUF-branded with a frontispiece portrait of Mosley, describe a life of hard work— “ploughing again” —alongside milestones in Fascist history (4 October, 1936: “BUF London. Reds in full force. Big loss for Fascism”). Creasy, meanwhile, was an unrepentant Nazi and retained a thuggish scepticism about more thoughtful trends in the movement.

Even these men didn’t find it easy to carry the BUF message into the shires, however loudly they shouted about better wages and a repeopled countryside. One disheartened Blackshirt wrote to Saunders that “it is rather hard on me to be always getting these sneers and jibes… it is rather lonely for one Fascist in this district”.At Stiffkey in Norfolk, Henry Williamson, the novelist famous as the author of Tarka the Otter, having taken the trouble to paint a large BUF logo on one of his outbuildings, was outraged when locals promptly painted over it.

Even in Germany, with Hitler entrenched in power, a Nazi propagandist could find it hard going outside of the urban centres. “We’re no Hitlerites,” one Bavarian peasant farmer told a young Nazi emissary some time in the mid-30s. “They only have those in Berlin.” Other officials were openly disrespected or heckled out of town. This is not to say, of course, that the German peasant was a milquetoast liberal; only that the realities of farming life seem seldom to have found room for exotic ideologies of race and state (or for knuckling under to a government, whatever its creed).

***

Other right-wing ideological spaces of the inter-war English countryside are harder—or at least less comfortable—to align with modern-day equivalents. The prominent back-to-the-land mystic Rolf Gardiner formulated one such space, professing a socio-cultural philosophy that was at once Romantic, anti-science, anti-industrial, communitarian, backward-looking, resorting always to the sacred soil, rooted in folklore, tradition and ethno-nationalism. Gardiner’s feisty occupation of this territory is no less problematic than his influence on organicism and the Soil Association, of which he was a co-founder.

Gardiner wrote with disapproval in 1943 of the Englishman (meaning especially the English farmer) who, as “a practical man,” is “not led by ideas nor… by principles” but, rather, by the “glaring immoralities” of expediency and opportunism. Gardiner, like many in the inter-war far right, saw farming as a workshop, a testing-ground for the new ideals of Fascism. As well as the Kinship of Husbandry—a rural revival group founded by Gardiner along with Lymington and HJ Massingham, and a significant forerunner of the Soil Association—he was a member of Lymington’s Fascist, xenophobic and wildly crankish English Mistery. His own initiatives involved leading parties of healthful young fellows in regenerative winter hikes across south-west England, singing folk songs, breaking at “noonday” for bread and cheese, and whiling away the evenings with readings from Famine in England.

That the legacy of “back to the land” sits uneasily with many of us today is not solely down to Gardiner. Even those considered more or less politically mainstream in the movement were prone to sharp rightward turns: John Stewart Collis, author on rural matters and a pioneer of the ecology movement in Britain, rather cheerfully confessed to enjoying Hitler’s speeches and thrilling at the “historic drama” of it all, while the pacifist and ex-Marxist John Middleton Murry wound up defending Oswald Mosley (“the authentic successor of Winston Churchill”) and calling for democracy to “transcend itself”. When today’s call to “reconnect with nature” grows louder in left-progressive circles, it’s hard not to think of back-to-the-land and look somewhat askance. Words like “kinship” do not return to vogue by chance; turning on the radio to hear about the “wonderfully positive… English nationalism” of a celebrated nature writer (in the face of “wokey, snowflakey” objections) is not without its problems.

All historians of Fascism have at some point to come to terms with the fact that their subjects are in large part nonentities and cranks. There may well be very few degrees of separation—social, political, ideological—between the crank and the cabinet minister. Or of course there may be no connection at all. The point is that one can only know for sure in retrospect. This is true, too, in considering the landscape of the present-day far-right.

The contemporary Rural Conservative Movement (RCM), if it is a movement, is a movement of one man, Robert J Davies, who lives in Wrexham and moves primarily between his Twitter account and his website. There Davies sets out the RCM’s eight key objectives, which may well have found favour with Gardiner and Williamson and Lymington all at once (though on perusing the rest of his website they might wonder, who is this “great Canadian philosopher” Jordan Peterson, this Tommy Robinson, “one of Britain’s greatest defenders”, or this “ray of sunlight” Elon Musk?).Subscribe

Davies—to be clear—is a halfwit. If he weren’t, he wouldn’t fit so well into England’s heritage of ruralist Fascism, which has always spoken in the voices of both the church elder and the village idiot. So on the one hand we find in the RCM’s eight-point plan high-minded calls to promote “spiritual oneness with Nature”, protect the green belt and defend our rural heritage, and on the other we find “Defeat Multiculturalism and Woke”, “Ensure the primacy of British culture”, and “Seek to preserve indigenous population share”.

Fascist capture of the English countryside—the actual countryside, not the one imagined by Robert J Davies on his camping holiday—has never been complete, never even been close to complete, for all the best efforts of the rural Blackshirts and all the strange bucolic dreams of the Fascists in the market towns. Of course the countryside tends to be conservative, and to turn blue on election days; a progressive, liberal constituency doesn’t elect Andra Jenkyns mayor, as happened down in the Lincolnshire prairies last year. But it is always hard work for the hard-right out there. The Fascist machine does not do well over uneven ground.

The far-right in its modern form is energised primarily by hostility to the growing multiculturalism of our towns and cities (especially, of course, to multiculturalism in London, and most especially, most madly and gleefully, of all to multiculturalism in Sadiq Khan’s London). Should this reflexive anti-urbanism not find a ready market in the hard-pressed countryside? Perhaps—up to a point.

Fascism’s problem is this: it despises the city, but is of the city. Even in the 1930s Fascists had to practise special pleading, posing as “exiles from the soil” (forced by the System to have Pall Mall clubs and commuter-belt homes). The far-right realises eventually that urbanite beefs about ULEZ or Jews will carry you only so far, and that the Farmer Barleymow cosplay, the stout yeoman, sons of toil stuff, the easy sops about blood sports and windfarms, will take you only so much further.

HJ Massingham argued in 1942 that if society were “to go on living”, its movement would have to be “toward simplification.” Medieval society had it about right, Massingham said: aim for that. Part of this movement towards the simple—he called it “katabolic” —was a drift “from urban towards rural”. But try going out into the countryside now and telling people their life is simple. Although it wouldn’t quite fair to call Massingham a Fascist, Fascism is in all its varieties a creed of simplicity. Even when it’s dressed up and asked to pass as a political philosophy, it is simple. This can of course be a selling point; it may sometimes be the case that “simple” equals “easy”, and easy is good. People like easy, and so they should. But in a complicated society “simple” more often than not equals “stupid”.

The countryside is a complicated place—is many complicated places, fighting under the same flag—and it always has been. Perhaps this is why Fascism has always fallen short there, even after it’s found a foothold, a Tithe War, a Family Farm Tax, a Henry Williamson. They go there expecting to make long speeches to willing peasants. They are lost before they’ve even arrived.